CLIFFORD EVANS – Man of the Theatre

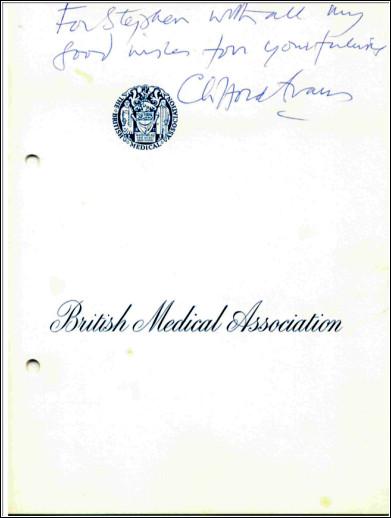

At a very early stage in my career as an actor, my father came home from a British Medical Association dinner with a menu signed by Clifford Evans. He had written “For Stephen - with all my good wishes for your future.” It was a sentiment Clifford Evans applied towards Welsh Theatre throughout his career. At the time, I am sorry to say, I didn’t know who Clifford Evans was and was totally unaware of his work as an actor and his struggle to give Wales the National Theatre he felt it deserved.

Clifford was born in Senghennydd in 1912. His father, David, was an outfitter and his mother a milliner. He came to Carmarthenshire to live with his grandparents when his father joined up and went to serve in the Great War. It was his grandfather who helped shape his values in life. Years before any aspirations to be an actor had formed, Clifford would entertain his grandfather with imitations of the Welsh preachers who came to Cwmdwyfran Chapel, north of Bronwydd. He would use old clothes and paint from a paint box to dress as a gypsy boy: a perfect opportunity for mischief with the neighbours, of which he certainly took advantage.

At eleven years old Clifford went to the Llanelli Intermediate School, joining his older brother Kenneth there. Clifford’s parents knew the value of this education as a stepping-stone to university and the career benefits they hoped that would bring. Cliff’s first taste of the acting bug came when his class performed a playlet called Pwyll a Rhiannon. This was followed by his involvement in several one-act plays. In 1926 Cliff’s Latin teacher, Dr Afan Jones, cast him in the annual school play, Bernard Shaw’s You Never Can Tell: parts in Oliver Goldsmith’s The Good Natured Man, J M Barrie’s The Admirable Crighton and a lead role in Shaw’s Pygmalion followed over the following three years. Apart from an early comment that Cliff tended to over enunciate, the reviews during those years moved from eloquent, graceful and a pleasing stage presence to excellent, magnificent immersion in character and a promising future. Cliff was now hooked. He wanted to be an actor.

When Cliff passed his School Certificate examination in 1928 he was fortunate to have the support of both parents in his career choice. The family home was now in Llanelli. His mother had worked in London for a time and loved the theatre. She decided that the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, RADA, was the best place for Cliff to study. A friend of Cliff’s father gave him a letter of introduction to actor Miles Malleson and, through an uncle, another letter to the critic, James Agate. On a misty February morning in 1929 Cliff and his mother left their Capel Road home and boarded a train for London to get him started. It was the day before his seventeenth birthday.

Cliff was already aware of a Voice and Personality contest being held at the Metropole Theatre and this was his first port of call. He registered his details, collected the audition texts and left to prepare for his appearance. The first prize was a film contract with British International Pictures. Cliff’s performance, with his mother in the audience, ensured his appearance in the finals a month later. They left their Russell Square B&B, his mother returned to Llanelli and Cliff moved into a one pound a week lodging in Hackney. With just ten shillings a week to keep him going, he ventured out to try to make good on the letters of introduction he had brought with him.

Seeking out Miles Malleson at the Royalty Theatre he found the actor kind and helpful. Malleson had studied at RADA and encouraged Cliff to go there to see the principal. He even offered to telephone in advance to support the application. Cliff wasted no time and was there within thirty minutes. Before Malleson telephoned, Cliff had auditioned and persuaded the principal to give him a special one term scholarship with a view to winning a full scholarship at the end of that term. He began classes that very day. Within six weeks Cliff’s mother and siblings had moved to London and, later, his father joined them. In those days names such as Bernard Shaw, Charles Laughton and Robert Donat were amongst the teachers and lecturers at RADA. They were happy days for Cliff. Another former “Intermediate” pupil, Professor Lloyd James who tutored BBC announcers, helped Cliff with his King’s English. Cliff subsequently won the Sir Johnston Forbes Robertson Prize for spoken English among other prizes and the RADA scholarship.

In 1931 Cliff made his first professional appearance, aged 19, at the Embassy Theatre in Swiss Cottage, London. He played Don Juan in a revival of The Romantic Young Lady. One magazine rated Cliff as one of several Welsh people lauded for their acting, and another as likely to make a name for himself. His next move was a tour in Canada and repertory at Folkestone and Croydon. In 1933 he made his West End debut when the Croydon production of Gallows Glorious transferred to the Shaftesbury Theatre. Reviews commented, “this performance alone is worth the admission money” and “sheer sustained acting and completeness of character drawing.” Although the play’s run was a short one it brought Cliff into the limelight. You might say that he had arrived.

In summer 1933, Cliff found himself playing the role of Everyman in Welsh, “Pobun”, at the Wrexham Eisteddfod. This was made possible largely by the work of Lord Howard de Walden, long an advocate and supporter of a Welsh National Theatre. De Walden had been behind the Welsh National Theatre movement of 1914, in which Llanelli’s Gareth Hughes had played a part. His productions were performed in Neath as well as Wrexham. One abiding thought that Cliff was left with was that a National Theatre could not be just a touring theatre. It needed a more solid footing than that.

As the fruits of Cliff’s West End debut ripened he was cast in John van Druten’s The Distaff Side with Dame Sybil Thorndike. They completed a three month run in London and toured to New York. Cliff and Sybil became fast friends, an enduring friendship. He taught Sybil Welsh. Sybil wrote of Cliff, “I felt, watching him, that here was a true actor” and “unforgettably lovely moments were in this performance”. On his return from America his next project was as Ferdinand in The Tempest at Sadler’s Wells, with Charles Laughton. He also played this at Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre. Further laurels came with his performance as Laertes in Leslie Howard’s Hamlet in America and as Oswald in Ibsen’s Ghosts at the Vaudeville Theatre, London.

Immediately on his return from Hamlet in America stories were circulating in the press that Cliff was to star as Lawrence of Arabia, in a film to be made by Alexander Korda. This never got off the ground. Cliff, however, was very busy as a film actor at this time. He appeared in nine films between 1933 and 1938 and another twelve between 1940 and 1943. He appeared in the Welsh coal mining picture Proud Valley with Paul Robeson in 1940 and starred with Tommy Trinder as the Foreman in The Foreman Went To France in 1942. This was an early Ealing Comedy, but more in the Music Hall tradition and bearing little similarity to the more famous, post war productions.

His career was partially put on hold in 1943 when Cliff, a conscientious objector, joined the Non Combatant Corps. He found himself directing and starring in productions at the Garrison Theatre, Salisbury for the Entertainments National Service Association (E.N.S.A.). He starred alongside Hermione Hannen, whom he had married in 1941. They had first met at RADA. He was also involved with the Army Bureau of Current Affairs (ABCA), which aimed to educate and raise morale among the troops. In the late 1940s there was a variety of work to keep him busy. He made two films, worked in radio, appeared in an All Star Matinee to benefit RADA, produced an opera, played Faust in Welsh and served on the Films Committee of the British Council (North Wales Office). Mr & Mrs Evans had a cottage in Buckinghamshire and an apartment in Chelsea. All was going well and there seemed to be nothing that Cliff wasn’t capable of taking on.

Bernard Shaw had taught Cliff that he should only tackle things he really knew about: a lesson Cliff valued. He always believed that a person’s background was precious, “something to be proud of, whatever it is, something that is a part of you”. He was once described as “one whom Wales can’t afford to neglect” and, in turn, he was not going to neglect Wales and, when the opportunity came, he stepped up to the plate. In June 1950, he accepted the Arts Council appointment to become Director at The Grand Theatre, Swansea for six months. He wanted to make it a nucleus of a Welsh National Theatre, ever a dream of his. Richard Burton came to play Konstantin in the first Welsh run of Chekhov’s The Seagull. Kenneth Williams appeared too, very much a serious actor then. Although Cliff and the season went well, the Grand was a large theatre to fill. Audiences per performance or play were rather good but, as a percentage of available seats, it didn’t match up and Swansea Council wasn’t keen to continue the project.

In 1951 Cliff engaged in another Welsh event. As part of the Festival of Britain, Cliff directed the Pageant of Wales, Land of My Fathers, in Sophia Gardens, Cardiff. Glyn Houston was the narrator. Cliff had devised and contributed to the script, which took Wales from King Arthur through to the Welsh pits, capturing the heart and soul of Wales. It was a stepping stone and in the capital city, the only place Cliff believed a National Theatre should operate. He also felt that there was little future for Welsh playwrights until they had a theatre of their own.

For the next five years Cliff became a busy film actor again. He made eleven films in those years, but no title you would instantly recognise. By 1957 he was publicly outlining the need for a National Theatre and, in 1959, formed the St David’s Trust with the objective of fulfilling his dream. His main companions in this goal were playwright Saunders Lewis and Lord Aberdare. The list of those who pledged support was heavy with names of the most talented and successful writers and performers: there were Sirs Donald Wolfit, Lewis Casson, Tyrone Guthrie, Malcolm Sergeant and Carol Reed; Richard Burton, Peter O’Toole, Stanley Baker, Harry Secombe, Meredith Edwards, Hugh Griffith, Kenneth Williams and Donald Houston; Sian Phillips, Dame Sybil Thorndike and Dame Flora Robson; Emlyn Williams, Alun Owen and Christopher Fry. The list was powerful. Meetings with Cardiff City Council progressed and locations were discussed. The Welsh Committee of the Arts Council, however, was following a different agenda.

Cliff and his colleagues had formed a plan for a nine hundred seat theatre, an art gallery and restaurant, rehearsal rooms and a two hundred seat student theatre. At the rear of the building, behind the main stage, an outdoor venue to accommodate two to three thousand people. This was all designed, worked out in great detail and to be built in Sophia Gardens, adjacent to the castle. This wonderful centre was to encourage Welsh talent, to develop a “vigorous, native style in production and performance”, creating opportunities in both Welsh and English. It was an extremely uphill struggle, though.

In 1962 the Arts Council created the Welsh Theatre Company, which was seen by many as overfunded for the return it gave: very few Welsh actors were used in its English productions. In spite of the difficulties, in 1963 Cliff thought the National Theatre might become a reality by 1966. The following year, in a very controversial move, the Welsh Theatre Company decided to call itself the Welsh National Theatre Company. The Board or Court of Governors of the proposed National Theatre believed that only they should approve such use of the word “National”, but to little avail. By the end of the sixties the dream was in tatters.

Cliff had devoted most of his acting talent since 1955 to television roles and this continued until 1978. Between 1965 and 1969 he became a household name in The Power Game. He appeared in Armchair Theatre, Dr Finlay’s Casebook, The Prisoner, The Avengers, The Saint and Jason King among many other well- known programmes. Clifford Evans never became a “star” as did many of his contemporaries. It is interesting to note that nobody has ever written his biography. He did, however, make an immensely important contribution to the worlds of theatre, film and television. The list of luminaries with whom he performed and collaborated is vast, far too weighty to include them all here. He was, truly, a very fine actor, but perhaps his choices prevented him from becoming more than that. It will ever be to the detriment of Wales that his dream of a National Theatre did not succeed. Clifford Evans died in 1985. He was a consummate professional and a consummate Welshman.

[Based largely on the Clifford Evans Papers at the National Library of Wales - This short biography was written for Llanelli Community Heritage and appears on their web site]